Every show is a story.

The above statement isn’t just true for plays or operas or things that are intended to tell a story. All types of shows, like stories, have common elements: They all have a beginning, a middle, and an ending, and stuff happens during all of that time. They have characters that interact with each other and their environment. They all have some kind of message, even it that message is subtle or simple. In the case of a concert, the story is usually carried by the feel of the songs that make up each set. ‘Set’ is the perfect word to describe this, because each set is its own mini-show, and then you put the sets together to create the overall show, with the story being carried throughout.

Building successful sets is not randomly choosing songs, it’s craft. You’re not just playing a bunch of songs–you’re telling a story. More importantly, you get to control the feel of your show and influence how the audience will perceive it.

These points are concepts to use, not a script to follow. As we go through the following points, remember that no two shows are alike and that the choices you make should be based on what you want your show to do.

Managing The Energy

Well-crafted sets lead the audience through a continuum of energy levels, emotions, and experiences. Changes in the energy are what will tell the story. Before you start plugging in songs, think about what the show’s overall energy curve looks like. Draw it out if that helps. Always keeping this curve in mind will make building your set a lot easier, because it reduces the number of variables you have to consider at any one time.

Beginnings

Do you want a big, punchy beginning or something dramatic that pulls the audience into the world you’re going to create for them? Will your act be mellow, upbeat, funny, somber, or…? Whatever you choose, your beginning needs to get the audience’s attention from the first note. In most concert settings, the audience receives cues to settle down and pay attention–like the house lights going down, the walk-in music fading out, etc. Your listeners are poised and prepared to dig your show, and you need to take full advantage of their attention before it’s gone.

Try not to talk to the audience as the first thing you do, unless your act is about talking–if you are a comedian or storyteller, for example. Even in those cases, there is often some element that sets the mood: A quick music intro or a lighting effect, that sets the tone for the audience. As a musician, your first song should do that job. The audience came to hear your music, so give it to them right away.

How many songs you do before you take a break to say hello is up to you, but try not to go on too long without acknowledging the audience. People like to feel included in the show, and their sitting in the dark watching you is not going to make that happen. Audience interaction is a part of your set, and it should be built into the sequence of events just like songs are.

Transitions

Humans don’t like sudden changes. As you plan your set, try not to put a slow song right before a fast one, and vice versa. Make the energy changes in each set smooth and fluid. When you make your energy graph, that line should be a graceful curve rather than a jagged, spiky scrawl. This is a ride and if it’s too rough, the audience will fall off and you’ll have a hard time getting them back on until the next set.

A note about art – Remember these are guidelines, not rules. If your show is intended to jar the audience and make them feel uncomfortable at times, that’s fine. If you are doing a more artistic show, you will probably want to make your energy curve much more detailed, more like a play script.

Endings

What do you want the audience to be feeling as they exit the room? This will depend on why they’re leaving (intermission or end of show), but most elements are the same in both cases. You always, always, always want to leave them wanting more. As soon as someone feels they’ve gotten all they want, they will leave. This is why big-name acts always put their biggest hits at the end of the show.

When you’re going to intermission, you really want to focus on making your set sound finished, but not complete. Try to create the idea that there’s more to come in the next set, and it will be even more amazing than the first one. Never put your strongest song in the first set, unless you are only playing a single set. Once you’ve shot your best arrow, everything else will be downhill and you want the overall show to build to a spectacular climax, just like any other story.

The end of your show is what people are going to take home with them, no matter what else happened that night. This is a very powerful element, so use it wisely. Do you want them happy? Then play something that will send them out singing along or all ramped up from your big finish. Do you want to make a point? Play something that leaves them hanging in some way–but be careful, if you hang them out too far, they won’t like it.

Song Selection

Which songs go in the whole show? What song goes in what set? Those are completely separate questions and should be answered in the order you just read them. Pick your best material to go in the show, and once you’ve created that list you can then start figuring out the order. If you try to do both tasks at the same time, you will never be able to decide on anything because there are still too many variables.

Be flexible! While the above rule is very helpful, you should always be willing to make a change if you get a good idea, or if circumstances prevent you from using a particular song and you have to swap something out.

Key variety

Even if your audience has no other musicians in it, they will still get bored if you play the same key over and over again. As you build your set, be mindful of putting songs together that are in the same key. If it turns out to be the best choice that’s fine, but avoid it if possible. If you need to put like keys together, try to pick songs that don’t sound the same. Combine different tempos, instrumentation, or other elements to keep things interesting.

Building The Set

Everyone has their own system, but here’s the one I use:

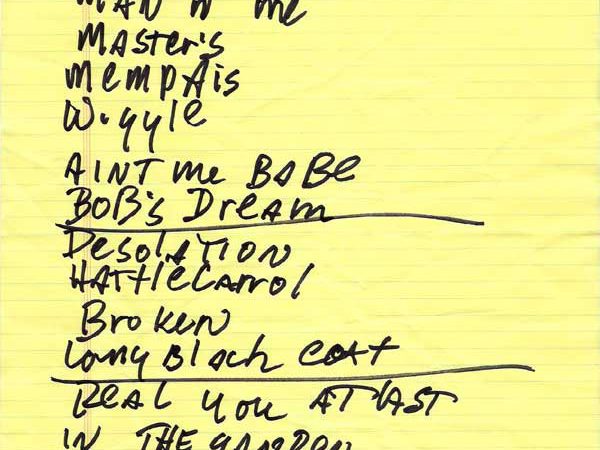

Step 1 – Assign anchor points. My band might have a song that is really strong and works very well at the end of a set. I will lock that song into that position and not move it. Or we might have a song that helps the vocalist warm up, so it goes in the first set. Or on the other side, maybe there’s a song that tires someone out and needs some kind of rest after it. In each case, those songs would be locked into specific positions, and other songs are then filled in around them.

This principle can apply to blocks of songs as well. Let’s say your band has this awesome roll-through from one song to another, and it always works out great. When you plan the set, you will treat those two songs like a single block and move them around together.

Step 2 – Assign sets. Of the songs left to place, which one goes in which set? This is where I do the bulk of my energy management, thinking about how I want each set to feel and how I want the audience to feel as the show goes on. In a lot of cases, all you can do is make an educated guess about how the show will actually play out. Don’t freak out when things don’t go according to plan–that’s what show business is all about!

Step 3 – Segues. How do the transitions sound between all the songs? I will often make a playlist in my favorite media player and manipulate the order of the songs, then listen to just the transitions–the end of one song going into the next one, to get the feel of it. I trust my instincts and experience to know when it’s right, but like everything else it takes practice and constant monitoring.

This is the point where I start to fine-tune the energy flow. Sometimes I work on energy first and then segues, sometimes the other way around. This usually depends on the type of gig and what the role of the music will be.

Step 4 – Technical details. Are there any events that will affect the flow of these songs? For example, if someone needs to change instruments. Where are there dead spots that need to be filled? What will they be filled with? Some choices are audience interaction, a vamp under band introductions, songs with a reduced lineup, etc. Each event is placed into the set list so it ends up reading more like a theatrical cue sheet. It’s important for everyone in the band to know what’s supposed to happen next so that they can look polished and prepared.

Step 5 – Fine tuning. Make sure there’s variety with keys, look for any repetition of style or lyrics…anything that could end up boring the audience. In this step I am listening to my playlist in more detail, trying to pick up the feel of the set and the show in general.

Step 6 – Feedback. I always send proposed set lists out to the band just to make sure I haven’t missed something. Each person has their own needs and concerns, and it’s important that those are properly addressed. Plus, I don’t believe I have a corner on building the perfect set!

This is not a fully democratic process. Each band will find its own system, but in general there is a single leader who makes the bulk of the decisions. The point here is that if you’re the person writing sets for your band, you will probably always be the go-to person doing that job. It’s wonderful if these types of duties can be shared, but humans are often pretty lazy and will not go looking for work if they don’t have to.

Practice & Listen

Practice your set in order as much as possible. For bands who play a lot of gigs, this is not as important. But here at Bandmakers, each band is playing one show, which is to their advantage since they get to practice as they will perform and don’t have to worry about mixing up the order of songs to suit different audiences.

Record your rehearsals, especially ones where you are running your set in order. Then go back and listen with the audience’s ears. That can be hard, since you’ve heard these songs a million times already. But for the audience, this is their first time and you want them to enjoy it. Unlike rehearsal, you don’t get any “do-overs” so you want things to go as smoothly as possible. How do you do that? The same way you get to Carnegie Hall: Practice, practice, practice.

About the author

Jim Dorman has been working in show business for nearly 40 years, both backstage and on stage. In addition to teaching music, he also gigs as a solo musician and plays bass with The Purple Herons. He is the founder of Tux Cat Music, which provides a wide variety of services to musicians at every level.

Jim Dorman has been working in show business for nearly 40 years, both backstage and on stage. In addition to teaching music, he also gigs as a solo musician and plays bass with The Purple Herons. He is the founder of Tux Cat Music, which provides a wide variety of services to musicians at every level.